About 2/3 of the population attaches importance to the ecological balance of their purchases. Nevertheless, hardly anyone is likely to know the CO2 footprint of their last purchase. We are tackling this issue and have developed a plan to change it. Let’s take food retailing, for example:

- The production of standard packet of butter produces around 6 kg of CO2, rice has a similar carbon footprint in terms of CO2, while pasta emissions are roughly equivalent to its own weight and the potato is a real climate saver. But who is aware of this when they go shopping every week? Who knows the climate balance of vegetables, frozen pizza, and bread?

- The following is sufficiently proven: Man-made climate change is real and directly linked to the emission of greenhouse gases (GHG). It is also known that corresponding measures are demanded by science, desired by society, and thus – sooner or later – demanded and promoted by politics.

The causality of climate change, societal interests, scientific goals, and political measures will be one of the most important factors for economic success in the next 20 years.

The customer plays a fundamental role in this. The demand for ecological products is evident across all industries. Flight safety, green power, and electric mobility will fundamentally change their industries. The consumer goods industry recognized the eco-trend at the latest with the emergence of LOHAS (Lifestyle of Health and Sustainability) over 10 years ago and reacted to it with sustainability initiatives. However, there is a clear imbalance on both the supply and especially the demand side. 73% of the population would probably or definitely change their consumption behavior for a lower environmental impact, yet a 125 billion € turnovers in the entire food trade is compared to only 12 billion € for organic food – despite a doubling of the turnover with organic food within the last 10 years. There are several reasons for this imbalance:

Information overload: There are about 20 different seals of approval in the German food industry with an awareness level of over 10% and a wide variety of meanings, which have to be researched extensively. Too much information often leads to passivity.

Organic is expensive: Depending on the product, organic food costs many times more than the “cheap version”. A less than 30% surcharge is an exception. Many people cannot afford “organic”, some do not want to afford it – also due to the lack of transparency.

The complexity of sustainability: Sustainability has many facets. Within the three pillars of ecology, economy, and social responsibility, there are a large number of sustainability criteria which – depending on the industry, product, and target group – have to be assessed differently.

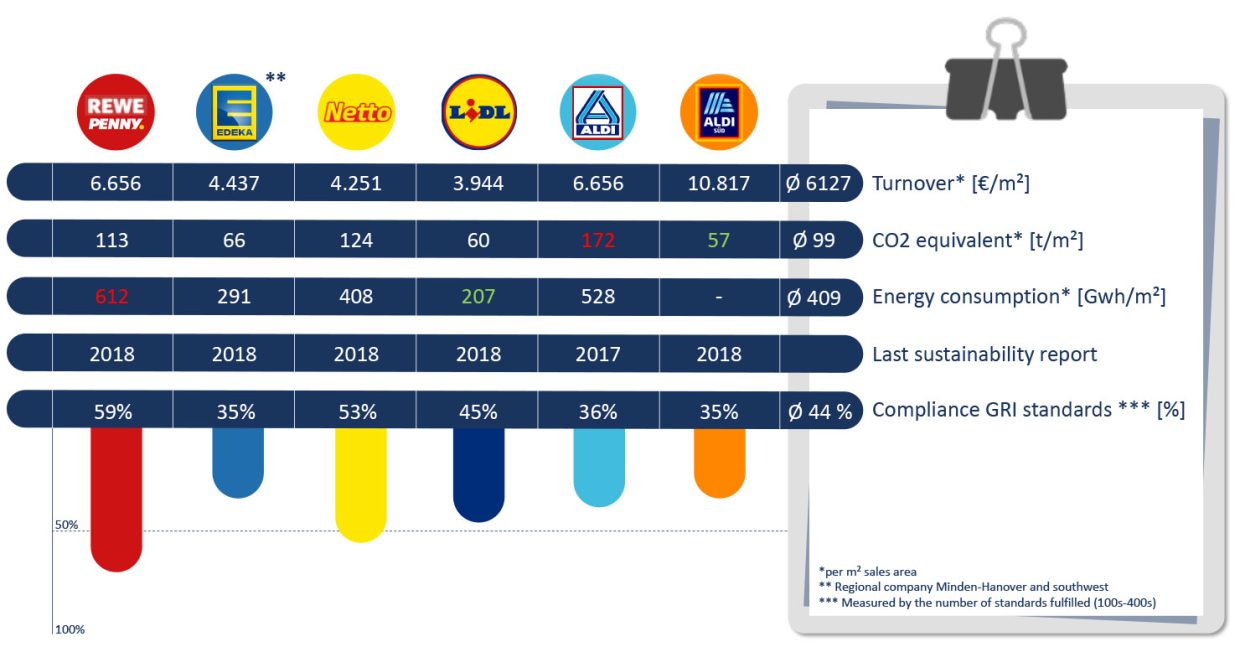

The heterogeneity of sustainability prevents comparability. P3 has developed a benchmark of supermarkets and discounters based on sustainability reports in retail. For this purpose, we have put factors such as energy consumption and GHG emissions into relation with the sales area.

FOOD RETAILING IN COMPARISON

It was shown that, for example, consistent tracking of energy consumption and GHG measures implemented by Lidl pays off. An examination of the use of GRI (Global Reporting Initiative) indicators also revealed a heterogeneous picture. While Edeka and Aldi Süd use only 35% of the relevant GRI key figures, the REWE/Penny report refers to 59% of the standard. We already considered greenhouse gas emissions as an important criterion in the benchmark.

The determination of the Product Carbon Footprint (PCF) offers several advantages with regard to ecological and economic actions. On the one hand, the PCF enables transparency and comparability for customers, and on the other hand, due to the CO2 pricing, it offers risk minimization for food producers and retailers.

This is because the direct link between climate change and greenhouse gas emissions enables political controllability. National and international CO2 budgets form the mathematical basis and the derived CO2 price functions as a climate policy instrument.

Political interventions for CO2 pricing have been under discussion not only since the European New Green Deal. Both an emissions trading system (EHS) and a CO2 tax are existing environmental policy instruments. While the CO2 tax is limited to individual countries, the European emissions trading system focuses on power generation and some energy-intensive industries with a total of almost 11,000 plants.

In 2010, at the 16th UN Climate Change Conference in Cancún, 194 countries agreed to the “two-degree target”, and five years later, at the Paris Climate Change Conference, 195 countries agreed to tighten it to “well below 2°C, preferably 1.5°C”. In order to achieve this, Germany will retain a CO2 budget of 4.2 billion tons of CO2 from 2020, based on a distribution key by inhabitants. This leads to a CO2 price of 70-130€/t CO2 in 2030 in the non-EHS sectors. By June 2020, the CO2 price for EHS certificates is about 25€ /t CO2.

Until now, the consumer sector has largely been left on the sidelines when it comes to climate policy intervention – that is about to change.

The Fuel Emission Trading Act extends CO2 pricing to the transport and building sectors from 2021. In addition, agriculture, in particular, is the focus of climate policy activities, which will have a direct impact on many food prices.

The European Commission has also recognized the importance of organic food for science and customers: “Citizens’ expectations are evolving, which is leading to significant changes in the food market. On 20.05.2020 the European Commission adopted the “Farm to Fork Strategy” as part of the New Green Deal.

In this strategy, the EU Commission confirms to reward those actors in the food chain who have already made the transition to sustainable practices and to enable others to make the transition, as well as to create additional business opportunities. It also states: “Through legislative and other initiatives, the strategy will work to ensure that the food industry takes concrete action to facilitate healthy and sustainable consumer choice”.

Companies in the food industry that are currently adjusting to CO2 pricing will benefit from this in the future. The prerequisites for this are available in the form of standards and technology.

Product carbon footprints can have complex dimensions. A decisive factor is the number of players along with the raw material extraction, production, trade, and sale to the end consumer. We recommend that retailers first focus on private labels in order to have direct access to the upstream. In relation to the PCF of a specific product, the following applies: first create transparency, then avoid and reduce CO2 emissions and only compensate for the absolutely unavoidable emissions.

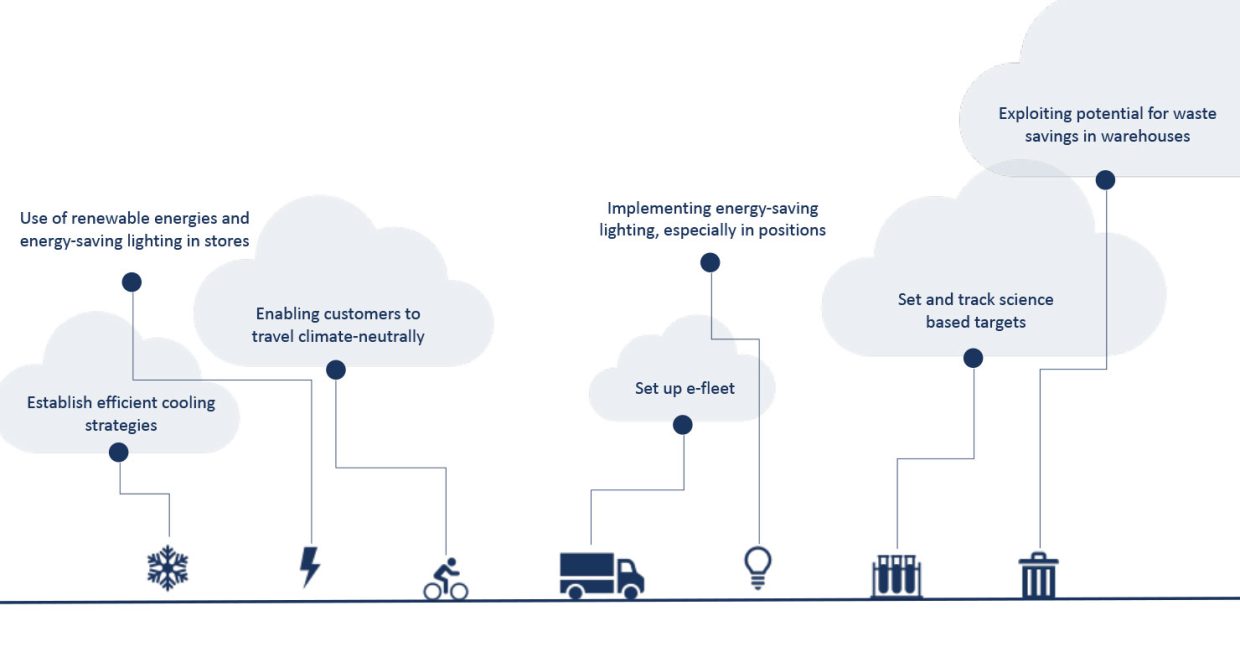

Besides the step-by-step procedure and the already mentioned focus on the PRODUCT CARBON FOOTPRINT, the following has to be considered:

ESTABLISH CREDIBILITY

Scientific findings apply to climate change – and so do measure against climate change. CO2 targets should therefore also be based on these. Organizations such as the Science-Based Targets Initiative (SBTi) promote such an approach and offer support in defining and validating targets.

DRAWING ON EXISTING BEST PRACTICES

There are a number of standardized procedures for the assessment of PCF and climate neutrality. Among the best known are the Greenhouse Gas Protocol (GHG), as well as the standards PAS 2050 and ISO 14067, which offer a methodical approach and thus efficiency in product evaluation. They also increase the comparability between products and thus the production and supply chain. In the consumer goods sector, a particular advantage is the higher credibility with the end customer through the use of established standards.

PRODUCERS, DISTRIBUTORS, AND RETAILERS ACTING AS PARTNERS

Sustainability is not a one-man show. CO2 transparency requires the participation of all actors along the up-and downstream. Upstream, common methods, and secondary data must be agreed upon. In the downstream, primary data can be collected to cover the entire life cycle. By using common data sources, structures, and methods, initiatives along with the production, supply, and trade chain can be implemented and evaluated more efficiently.

INITIATIVES FOR SUSTAINABLE FOOD RETAILING

TAKE ACCOUNT OF PROFITABILITY

Many sustainability initiatives have a positive financial impact in the long term – but not all of them! Initiatives must therefore be examined in advance in terms of costs and benefits. The Sustainability Initiative Index (SII) compares the financial and environmental effects of an initiative.

USING DIGITALISATION

Digitization enables transparency and complexity handling along the entire product life cycle. For example, blockchain technology is already used in supply chains. Hyperledger blockchains can be used to track not only CO2 emissions but also other sustainability aspects such as working conditions.

In the front-end, apps offer the possibility of easy integration of upstream and downstream actors. P3 has designed an app and developed a prototype that allows every customer to see, optimize and offset the carbon footprint of their purchase.

CREATE CUSTOMER EXPERIENCES

As an essential driver of the sustainability trend, the customer is now being neglected in many areas of sustainability. CO2 transparency enables a new dimension in food purchasing. Example: Gamification approaches allow customers to compete with their friends and supply chain transparency brings consumers and producers closer together.

CONCLUSION

The CO2 issue also affects the consumer goods industry. This is the only way to achieve the scientific, political and social goal of climate neutrality.

So far, activities to optimize the CO2 footprint have mainly concerned logistics and building infrastructure. However, for customers of consumer goods, the CO2 footprint of the product is decisive.

Companies that are starting or have already started to optimize the carbon footprint of their products today will improve their customer image in the short term, efficiently meet political requirements in the medium term and strengthen their market position in the long term.

A number of factors need to be taken into account when establishing the Product Carbon Footprint. These include the involvement of all players in the product life cycle and the use of established standards and new technologies.